Stimulant treatment

Treatments for addiction problems have much in common regardless of the substance. A general, stepwise approach is…

① Stabilisation

② Relapse prevention

③ Lifestyle change

④ Harm reduction

What are the effects of stimulants?

Stimulant drugs have similar effects: they create a sense of exhilaration and tremendous well-being, accompanied by physical arousal. Practical uses are to increase alertness, attention, and physical performance. In high doses they may cause confusion, delirium and paranoia.

Naturally occurring stimulants are caffeine, found in coffee, tea, and chocolate, and nicotine found in tobacco plants.

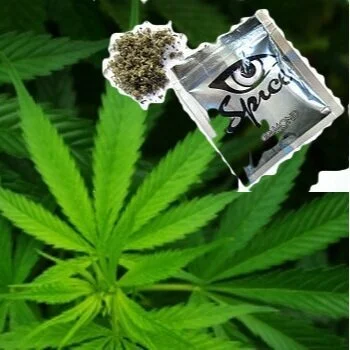

Cocaine derivatives are chemically processed from the coca plant; CRACK cocaine is more potent.

Amphetamines include the medicine Dexedrine and methamphetamine.

Entactogens such as MDMA (Ecstasy) or mephadrone are synthetic amphetamines with mild psychedelic properties, notably increasing empathy and a sense of being at one with others.

There is limited research on treatments for stimulant dependence.

Stabilisation

Stimulants vary in potency from caffeine to ‘party drugs’ to the most potent cocaine and amphetamines. The more potent drugs can be self-limiting in their use. People may be taking them for fun, at a festival for example, and so have a definite time to stop using but regardless of why stimulants are taken people tend to ‘burn out’ - it is too much to be constantly hyped up.

Abstinence (detoxification)

On stopping stimulants there is an abstinence syndrome rather than the bodily hyperactivity of a withdrawal syndrome as experienced with heroin or alcohol. The abstinence syndrome occurs because constant use of stimulants depletes the brain’s neurotransmitters. Symptoms include agitation, increased appetite, depression, and insomnia with unpleasant dreams, craving and physical discomfort. This phase usually lasts about one week but may stretch to three weeks. Symptoms of moderate cognitive dysfunction, depression and anxiety, emotional dullness and cravings may persist for around six months.

Most people just stop their stimulant use. Symptomatic relief of mood disturbances, anxiety or depressive thoughts, and insomnia can be helpful.

Cocaine is converted to benzoylecognine which can be detected in urine for up to 2 days. Elimination of amphetamine varies markedly depending on the acidity of the urine.

Cutting down

Where stimulants are taken as recreational drugs then reducing use is likely to follow cutting down on those activities where drugs are taken. Where there is dependent use of potent stimulants then reducing use is unlikely to happen, rather burn-out will result in a break in use, albeit brief. For stimulants such as caffeine or nicotine, cutting down can be a ligitimate part of a treatment plan.

Relapse prevention

The craving for stimulants and possible pressure from suppliers to keep their customers addicted make it difficult for both recreational and dependent users of stimulants to abstain or moderate use. What might trigger further use?

in the short term

low mood with suicidal thoughts

a lack of distracting activities

unappealing ways of satisfying increased appetite

in the long term

personal high risk situations

Rating high risk situations is the first task in a relapse prevention programme. Once identified and rated for the degree of temptation and the individual’s belief in their coping ability, new coping strategies can be identified, practised and implemented in real life.

Coping skills is a core session of iSBNT…

Relapse prevention medication...

There is no convincing evidence to support pharmacotherapies for cocaine or amphetamine abstinence syndromes.

Medications that have been evaluated include: topiramate, mazindol, dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate, modafinil and bupropion.

STOP SMOKING clinics have well established programmes, including medication, to help with smoking cessation.

Any prescribing will be for symptomatic relief.

Lifestyle change

It is only feasible to get on with the challenge of lifestyle change, which may include sorting out mental health issues, once a person has some control of their opioid use, and can be quick to achieve. Social treatments are most likely to be effective, not just for problem users but also for their family and friends, but other approaches can be effective provided that they are well structured and well delivered. Contingency management and day or residential programmes are effective for the more dependent users.

Harm reduction

Generic harm reduction measures to improve health and wellbeing are to be applied throughout treatment. There are no specific harm reduction measures for stimulant use.

effective interventions…