Psychedelics Treatment Outcomes

selected research articles

Psychedelic drugs taken for recreational reasons are, with the possible exception of ketamine, not especially difficult to give up or use in a controlled and safe way. There are no specific treatments for psychedelics and so, where their use becomes problematic, social support is key to the success of treatment, and, as with any other drug, it makes good sense to use a socially based intervention such as Social Behaviour and Network Therapy (SBNT) or the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA). Given that psychedelics are seen as mainly unproblematic, there is a lack of evidence supporting any interventions.

Psychedelics have been used to enhance spiritual arousal and for treatment of psychiatric disorders, notably depression, PTSD and obsessive compulsive problems, and for personal growth therapies, for which some evidence of effectiveness is available.

Survey :: lived experience of ketamine and help-seeking

Harding RE, Barton T, Niepceron M, Harris E, Bennett E, Gent E, et al. (2025)The landscape of ketamine use disorder: patient experiences and perspectives on current treatment options. Addiction 120: 1-10 doi.org/10.1111/add.70073

The participants were 274 individuals with self-identified ketamine problems, including both treatment-seeking, 40%, and non-treatment-seeking, 60%, current or former ketamine users and 59% reported a diagnosed mental health disorder. The average amount consumed was 2.0 grams per day. In spite of significant problems including an abstinence syndrome (see chart) the majority, 56%, did not seek treatment and of those who did two thirds cited health and being ‘sick of the lifestyle’ as reasons but only 36% reported feeling satisfied with their care.

Pharmacotherapies

There are no standard pharmacotherapies for psychedelics and the available evidence is weak

Review :: ketamine pharmacotherapies

Roberts E, Sanderson E and Guerrini I (2024) The Pharmacological Management of Ketamine Use Disorder: A Systematic Review. Journal of Addiction Medicine 18: 574–579 DOI: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001340

Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria reporting on 368 participants. The limited very low-quality evidence, mainly case studies, suggests benzodiazepine regimens may be most suitable for ketamine intoxication and withdrawal, whereas case reports suggest naltrexone, lamotrigine, and paliperidone palmitate plus bupropion merit further investigation with regard to reducing craving and relapse prevention.

Other evidence

Important :: terminology to categorise psychedelics

Nutt DJ, Erritzoe1 D, Schlag A , Luke D, Mash DC et al on behalf of the Drug Science Medical Psychedelics Working group (2025) A lexicon for psychedelic research and treatment. Drug Science, Policy and Law 11: 1–8 DOI: 10.1177/20503245251380511

Amanita muscaria

Salvia divinorum

Atropa bella-donna

Psilocybe semilanceata

Claviceps purpurea

Historically and to the present day psychedelics have been extracted from fungi and plants. The first semi-synthetic was LSD in 1938 - ‘semi’ because it was a chemical adaptation of the ergot fungus Claviceps purpurea. Phencyclidine was synthesised in 1956 as an anaesthetic and replaced by the safer ketamine in 1962.

This expert group present pharmacological classification system encompassing serotonergic, glutamatergic, kappaergic, GABAergic, and atypical psychedelics; dose-dependent categories, microdose, minidose, mididose, and macrodose, are introduced to standardise the description of dosing levels and intended subjective effect.

-

Agonists at the 5HT2 receptor eg LSD, psilocybin, mescaline. Antagonists are ketanserin, risperidone, olanzapine, mirtazapine.

-

Agonists at the GABA-A receptor eg the fungus Amanita muscaris. Potential antagonists are bicuculline, gabazine.

-

Agonists at the Kappa opioid receptor eg the plant Salvia divinorum. Antagonists are naltrexone, buprenorphine.

-

Antagonists at the NMDA glutamate receptor eg ketamine and phencyclidine.

-

Antagonists at the NMDA glutamate receptor and agonist at the Kappa opioid receptor eg ibogaine.

Discussion and review :: treating mental illness

Nutt D (2019) Psychedelic drugs—a new era inpsychiatry? Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 21: 39-147. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2019.21.2/dnutt

Vargas MV, Meyer R, Avanes AA, Rus M and Olson DE (2021) Psychoplastogens for Treating Mental Illness. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: article727117 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.727117

The use of psychedelics to treat mental illness or enhance insights from psychotherapy was popular in the 1960s but came to an end in 1967 when psychedelics were designated by the United Nations convention on drugs as having no medical uses and to be harmful. Nonetheless, psychedelics have continued to be used illicitly and reported not only to causes the desired psychedelic effects, but also to lift low moods and bring about lasting personality changes whereby individuals become more empathic and thoughtful. Recent studies have added weight to the effectiveness of psychedelics for the treatment of depression, anxiety, PTSD and addictions.

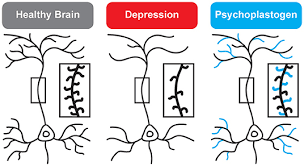

It is thought that the mechanism for treatment across such a range of disorders is the ability of psychedelics to rewire the brain. The graphic shows how connectivity between brain cells, neurones, is diminished in depression and rapidly restored by drugs such as psilocybin (called a psychoplastogen). Why then are these drugs not widely available for treatment? First, there is a lack of high quality research: large numbers of participants are excluded from trials because of risks from side-effects and trials are difficult to design. Second, treatments are not simple to administer, not cost effective and cannot easily be scaled up to meet demand.

addiction outcomes…